Future Black Hole Images Could Put Einstein’s Theory to the Ultimate Test

In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) released the first-ever images of a black hole. The resulting pictures, of a blurry orange swirl, were, in truth, images of the black hole’s shadow on glowing gas. That’s because a black hole is a total void from which no light can escape, including the light that would normally reach the telescope’s sensors.

Researchers show these “shadow” images can still be useful to science, in a new paper published in Nature Astronomy led by astrophysicist Luciano Rezzolla at Goethe University Frankfurt. The team has predicted that future images from the EHT will ultimately help the field test whether black holes stick to the tight tenets set down by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Read More: Colliding Black Holes Emitted a Massive Ringing, Confirming Predictions from Hawking and Einstein

What Do Black Holes Really Look Like?

Many different competing theories oppose Einstein’s view of the universe. In each of these theories, black holes will act differently on surrounding matter.

“Some of these approaches require the presence of matter with very specific properties or even the violation of the physical laws we currently know,” Rezzolla said in a press release.

Rezzolla and his team developed complex computer simulations that model these effects. They also outlined the performance level that future telescopes will need to achieve to determine whether an imaged black hole fits Einstein’s theory or one of the other competing solutions.

“The central question was: How significantly do images of black holes differ across various theories?” said study co-author Ahkil Uniyal, a researcher at the Tsung-Dao Lee Institute in Shanghai.

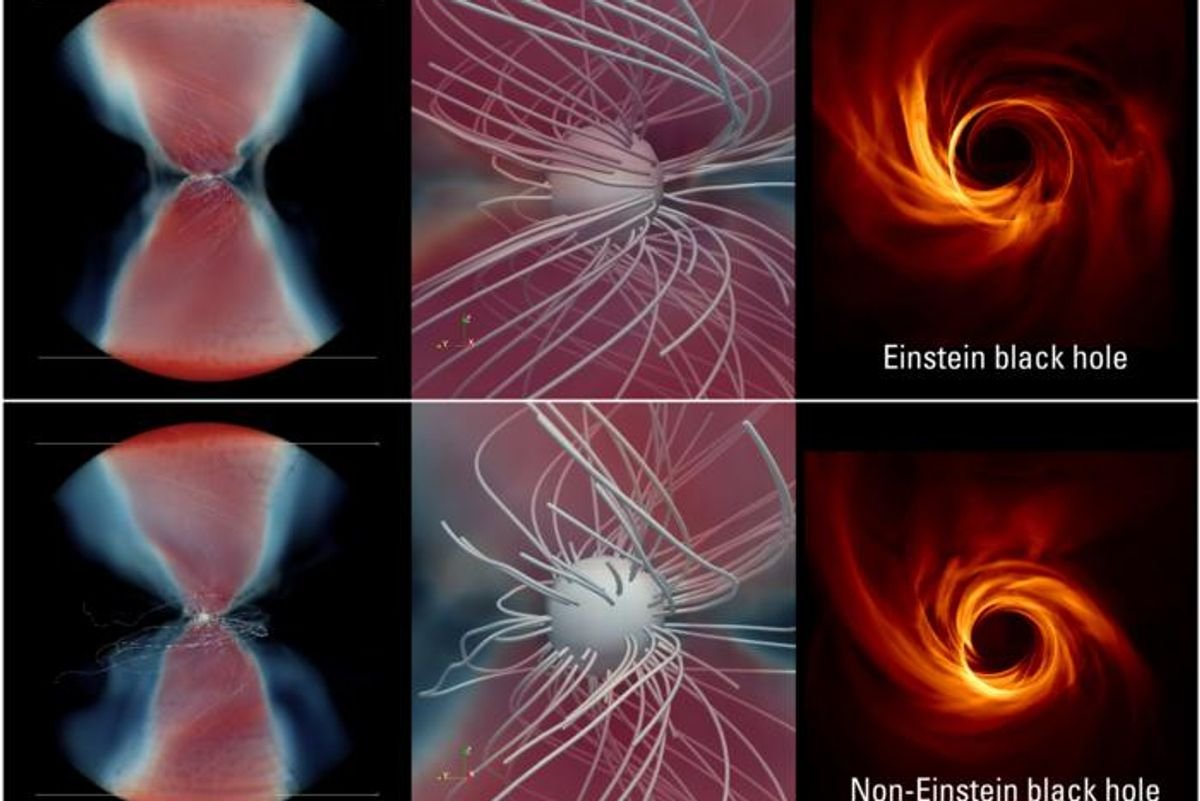

The team’s computer simulations, corresponding to each of the different black hole theories they tested, were used to generate synthetic pictures of how matter surrounding the black hole would be affected in each scenario.

Ruling Out Einstein’s Competitors

Einstein’s theory suggests that a black hole follows a Kerr solution, forming an asymmetric shape with an oblate event horizon. This type of black hole is named after New Zealand astrophysicist Roy Kerr, who discovered the exact spacetime solution for a rotating black hole under general relativity.

Rezzolla’s team was able to show, using their simulations, that if a black hole differs by more than roughly 2 to 5 percent from the Kerr shape, then future high-resolution telescope images should be able to tell them apart.

At this point, the EHT images have ruled out only the most outlandish black hole theories. Current images suggest that the black hole at the center of our Milky Way and that at the center of the M87 galaxy are unlikely to lack event horizons or to be wormholes (tunnels through spacetime that would allow faster-than-light travel).

Rezzolla’s theoretical work has outlined what future telescopes will need to test. Now, we must build them. The EHT is a collaboration between many Earth-based telescopes that feed into each other to enhance image quality. Future telescopes could be built in space to improve image quality. The resolution needed to tell black holes apart will be equivalent to that needed to see a coin on the surface of the moon. When the day comes that our technology is up to the task, Rezzolla thinks Einstein will once again be proved right.

“Our expectation is that relativity theory will continue to prove itself, just as it has time and again up to now,” he said.

Read More: Two Black Hole Mergers Emitted Gravitational Waves, Upholding Einstein’s Theory of Relativity

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: