A Growing Weak Spot in Earth’s Magnetic Field May Cause More Satellites to Short Circuit

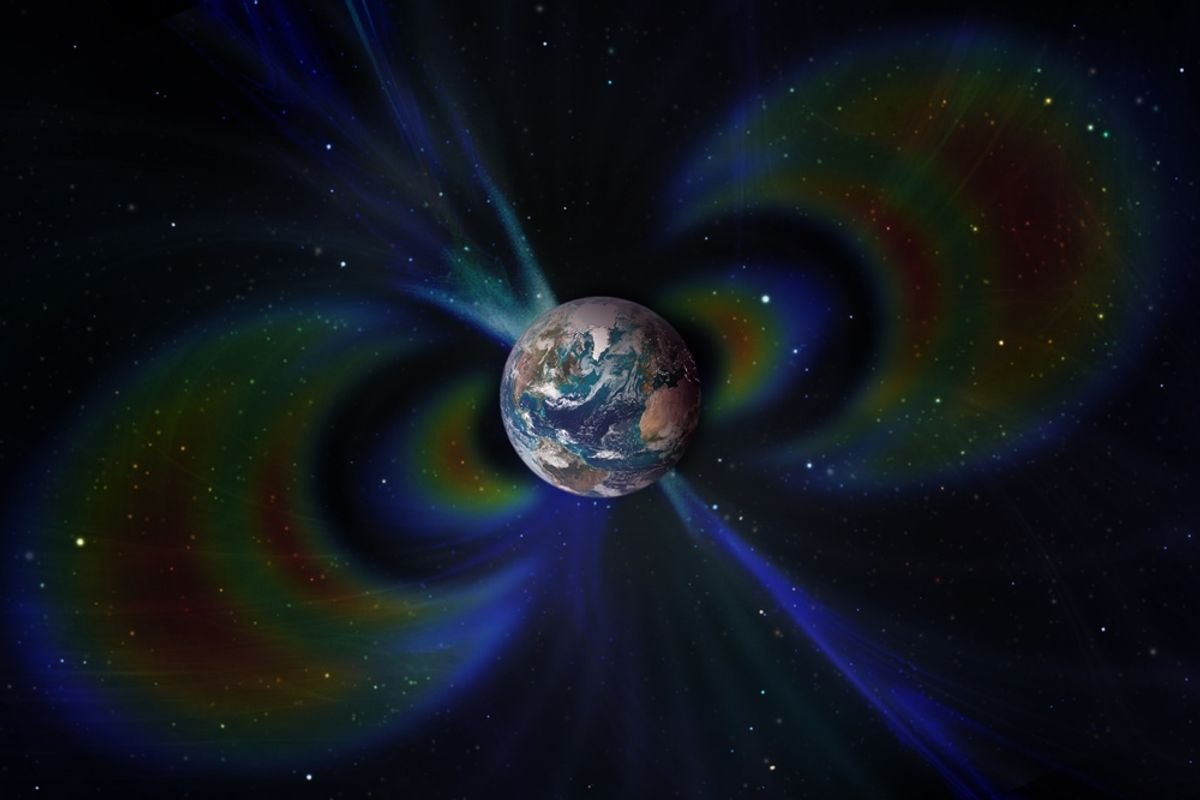

Earth’s magnetic field is like an all-encompassing shield, mostly deflecting charged particles that are launched from the sun. But this shield isn’t flawless; it has weak points that leave openings for cosmic radiation to strike, sometimes putting satellites in harm’s way.

One such vulnerable area is the South Atlantic Anomaly, a glaring soft spot in the magnetic field that has been steadily growing for over a decade.

A new study published in Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors has shared a snapshot of the South Atlantic Anomaly’s expansion, revealing that it has grown by an area nearly half the size of continental Europe since 2014. This and other trends across the magnetic field show how important it is to keep up with Earth’s ever-changing magnetism.

Earth’s Magnetic Field

The South Atlantic Anomaly (SAA), located over South America and the South Atlantic Ocean, was first identified in the 19th century. Since then, researchers have been paying close attention to the changes it has gone through over time. That’s because the SAA is one of the main areas where satellites in low-Earth orbit are exposed to significant doses of cosmic radiation, which can cause structural damage and electronic malfunctions.

The SAA exists in part because of the Earth’s tilt and the complex processes that shape the magnetic field, involving the flow of molten metals in the planet’s outer core. Another major factor is the SAA’s proximity to Earth’s inner Van Allen Belt.

The Van Allen Belts are two doughnut-shaped zones that wrap around Earth, trapping particles from either cosmic rays or solar wind. The SAA is where the inner Van Allen belt reaches closest to Earth’s surface, causing the area to be inundated with charged particles.

Read More: Van Allen Belts Are Dangerous Radiation Rings in Space – Here’s How Astronauts Get Past Them

A Weak Spot in Earth’s Magnetic Field

The new study has traced the growth of the SAA through satellite data that has been recorded as part of the European Space Agency’s Swarm mission. The mission, launched in 2013, includes three identical satellites (Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie) that measure magnetic signals emitted from the planet.

The satellites have observed steady growth of the SAA from 2014 to 2025. They’ve also spotted a particular region — over the Atlantic Ocean southwest of Africa — where weakening of the magnetic field has been especially prominent since 2020.

“The South Atlantic Anomaly is not just a single block,” said the study’s lead author, Chris Finlay, a professor of geomagnetism at the Technical University of Denmark, in a statement. “It’s changing differently towards Africa than it is near South America. There’s something special happening in this region that is causing the field to weaken in a more intense way.”

The pronounced weakening is associated with reverse flux patches, phenomena that represent atypical movement of magnetic field lines. These lines normally come out of the Earth’s core in the southern hemisphere, but in the SAA, they’re going back into the core. Right now, reverse flux features are moving westward over Africa, researchers say.

Earth’s Dynamic Magnetism

The SAA is not the only place where Earth’s magnetic field is experiencing change. The new study also examined fluctuations in two areas in the northern hemisphere where the magnetic field is particularly strong.

One is over Siberia, where the strong field region has grown by 0.42 percent of Earth’s surface area (around the size of Greenland). The other is over Canada, where the strong field region has shrunk by 0.65 percent of Earth’s surface area (around the size of India).

The growth in the magnetic field over Siberia, the researchers say, is related to the northern magnetic pole drifting toward that area, which will continue to impact navigation systems in the years to come.

Read More: The Magnetic North Pole Is Drifting Across the Arctic Toward Siberia

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: