When Will Earth’s Magnetic Poles Flip? Probably Not Anytime Soon — Here’s How We Know

Key Takeaways on Earth’s Magnetic Pole Shift

- When will the pole shift happen? Researchers say it’s definitely a matter of when and not if. The poles have shifted in the past and will likely do so again.

- When the pole shift occurs, it will happen slowly over thousands of years. When it does happen, life on Earth will likely not be greatly impacted.

- Earth is not overdue for a pole shift; it will happen when it’s supposed to happen. And when it does, those who live around the equator will likely be able to see auroras or northern lights.

In November 2025, residents across the U.S. were treated to a stunning, unexpected light show. A powerful geomagnetic storm, triggered by increased activity on the sun, sent shimmering auroras to skies as far south as Florida.

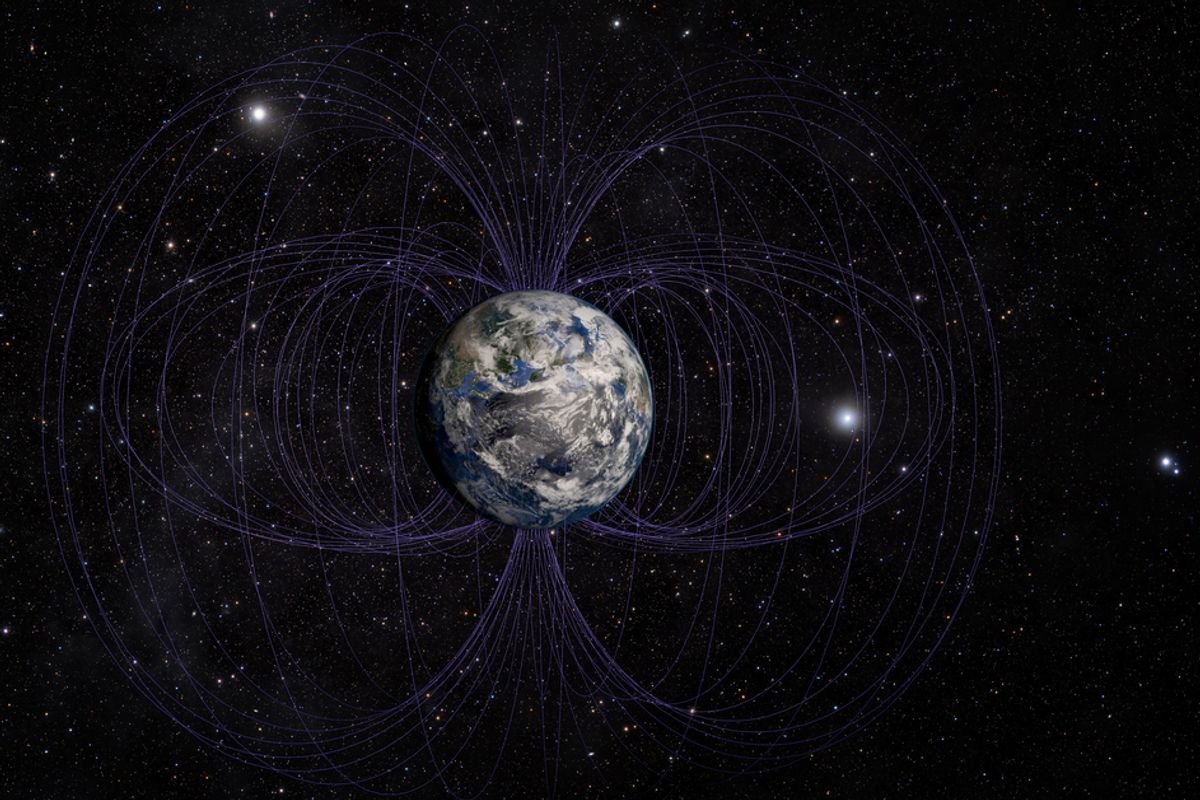

These auroras, or northern lights, occur when high-speed particles called solar wind careen into the Earth’s magnetic field. If it were not for this invisible shield, life on this planet would be vulnerable to the brunt of damaging cosmic radiation.

But much like our planet itself, this force field is constantly shifting. Evidence from Earth’s ancient history tells us a surprising story about this planet-spanning blockade; every so often, the field flips on its head, reversing the poles.

Some of these changes are even detectable scientific instruments, such as the South Atlantic Anomaly. This growing weak point exposes passing satellites to elevated radiation levels. Even stranger, scientists have observed our north magnetic pole moving toward Siberia at a blistering pace of over about 31 miles (50 kilometers) per year.

This motion begs the question: are we due for another reversal? And if so, what does it mean for our tech-dependent civilization?

Read More: How Does Earth’s Magnetic Field Work?

Will Earth’s Magnetic Poles Ever Flip?

Will Earth’s magnetic poles ever flip?

(Image Credit: Siberian Art/Shutterstock)

Despite their often-misunderstood nature, pole flips, or geomagnetic reversals, are a normal, recurring part of Earth’s history.

“It is indeed a question of ‘when,’ not ‘if,'” says Dr. Chris Finlay, a professor of Geomagnetism at the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) Space. “The geological record shows that Earth’s magnetic field has reversed many hundreds of times, and we have no evidence this has changed.”

These reversals come from the nature of our very core. Earth’s magnetic field is not generated by a static bar magnet like the one you would find in a fidget toy. Rather, electrically conductive iron in the liquid outer core flows with the planet’s rotation. Physicists call this spin-induced phenomenon the geodynamo.

A 2025 paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research found that this dynamic “boiling pot” model of our planet’s interior made random motions and reversals not only possible, but also likely over time. Some studies, like one in Nature Communications, suggest the solid inner core even wobbles between fast and slow-rotating periods, stirring outer layers and adding further instability to the mix.

Is Earth Overdue for a Pole Shift?

Despite reversals being a common occurrence during our planet’s past, and near certainty in its future, you probably shouldn’t be holding your breath waiting for one.

“No, we are not overdue for a reversal,” Finlay says. “Reversals of Earth’s magnetic field do not follow a simple repeat cycle. They instead occur unpredictably and are an example of a chaotic process.”

The intervals between these flips are therefore stochastic, or random. To test this, scientists applied statistical analysis to see whether the Earth would offer any signs of a pending shift. Their results, published in Geophysical Research Letters in 2023, found that reversals could only be reliably detected once already underway.

Even the so-called South Atlantic Anomaly might not be such an anomaly. A 2022 study from Proceedings of the National Academy of Science suggests these perturbations have occurred multiple times over the last 9,000 years and may be caused by nothing more than blips in our swirling core’s geometry.

What Would Happen If the Poles Shift?

Despite their sporadic nature, pole shifts are a very real phenomenon that weakens the Earth’s magnetosphere. So, just what would happen to our biosphere and fragile electrical societies if such an event occurred?

While a sudden magnetic reversal sounds like a compelling Hollywood disaster flick, the reality would likely be far less cinematic and much, much slower.

Some studies, such as a 2023 paper in the National Science Review, suggest that weakening caused by reversals could expose humans and wildlife to marginally elevated radiation levels, but the effects are poorly understood and certainly not a death knell for our species.

“One of the biggest misconceptions is that they would cause human casualties or even a doomsday,” says Dr. Hrvoje Tkalčić, a global seismologist and Professor at the Australian National University. “Our ancestors survived many previous flips.”

The most important factor is the timeline. “Although polarity reversals happen fast on geological timescales, they occur very slowly on human timescales,” says Finlay. “Previous reversals have typically taken around 10,000 years.”

The most meaningful consequences would be technological. As the field weakens, more high-energy cosmic rays would reach lower altitudes. “Low-Earth-orbit satellites would probably experience more energetic particles,” says Finlay. “This can be mitigated with improved shielding.”

Since the field changes over thousands of years, we would also have ample time to update our compasses and GPS systems. In fact, there may even be a bright side to the whole ordeal. “On a positive note,” Tkalčić says, “nations located at moderate and equatorial latitudes would experience auroras.”

Read More: Earth Actually Has Four North Poles

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: