The Universe’s Mysterious Little Red Dots Are Young Black Holes

Some of the faintest sources in James Webb Space Telescope images don’t fit neatly into existing categories. Appearing as compact red points in deep views of the early universe, they show up at very early times and then largely disappear a few hundred million years later.

A new study published in Nature now links those fleeting signals to a specific stage in black hole growth. Rather than marking massive early galaxies, the “little red dots” appear to be young black holes caught during a brief but intense growth phase, embedded in dense clouds of gas that alter how their light reaches us.

“We have captured the young black holes in the middle of their growth spurt at a stage that we have not observed before. The dense cocoon of gas around them provides the fuel they need to grow very quickly,” said one of the principal researchers behind the study, Darach Watson, in a press release.

Read More: Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity Helped Create Dazzling Simulations of Stellar Black Holes

What JWST’s “Little Red Dots” Really Are

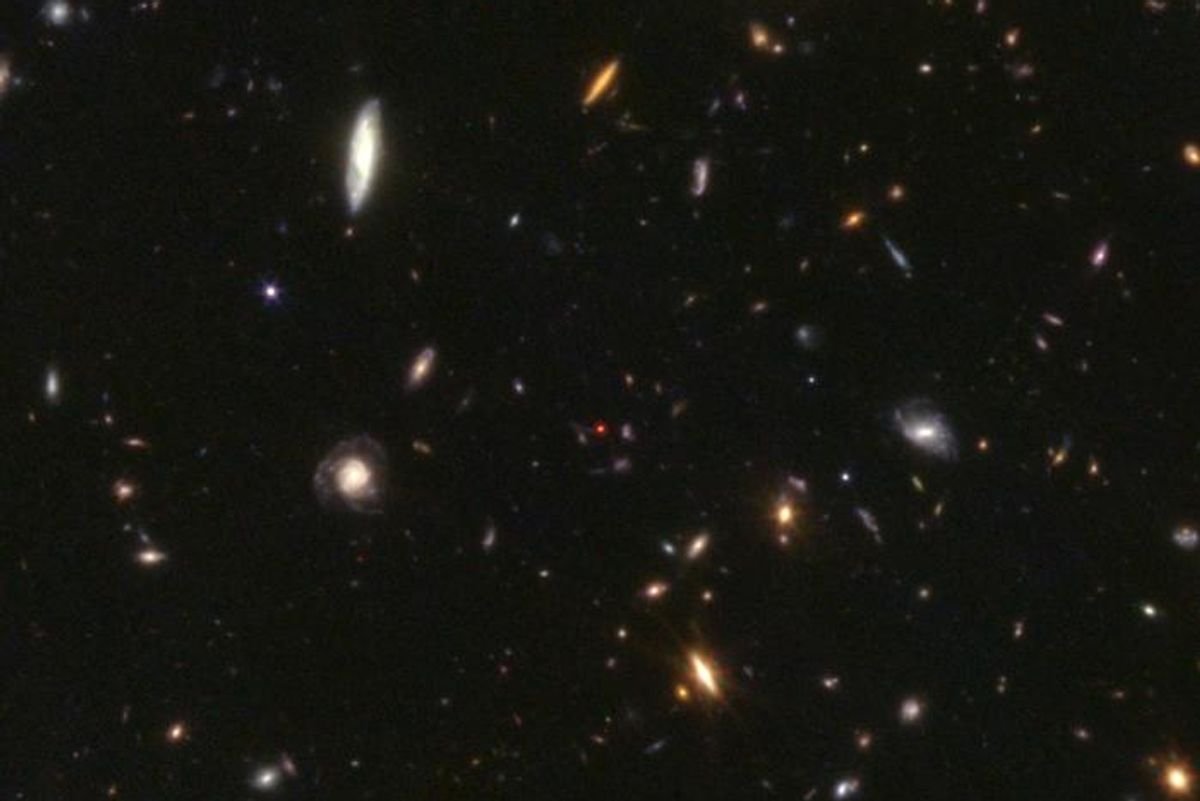

Little Red Dots captured by JWST

(Image Credit: Darach Watson/JWST)

The red dots first stood out because their brightness and color didn’t match expectations. Objects forming so early in cosmic history should either be dimmer or resemble star-filled galaxies that persist and evolve over time. Instead, these compact sources appeared briefly, then faded from view.

One early explanation was that the dots represented unusually massive galaxies forming far earlier than current models allow. But galaxies take time to build up stars, dust, and structure, and the timing didn’t add up. The new analysis instead points to a much more compact power source: black holes that are smaller than initially assumed, but actively pulling in surrounding material.

As gas spirals inward, it heats up and emits intense radiation. In these early black holes, that radiation is filtered through a dense envelope of ionized gas. Higher-energy light is absorbed and re-emitted at longer, redder wavelengths, giving the objects their distinctive appearance in Webb’s infrared images.

How Young Black Holes Grow Inside Dense Gas Clouds

Even as they grow rapidly, black holes are inefficient eaters. Most of the gas drawn toward them never crosses the event horizon. Instead, energy released near the black hole drives much of that material back out into space.

As infalling gas accelerates and compresses, it reaches extreme temperatures and shines intensely. Powerful radiation and magnetic forces then produce outflows that clear away surrounding material over time. This process both fuels black hole growth and limits it.

Although these young black holes are modest by cosmic standards, weighing millions of times more than the sun, they can briefly outshine entire galaxies during this phase. Once the surrounding gas is blown away, the black hole’s light changes character, and the object no longer appears as a compact red source.

What the Red Dots Reveal About the Universe’s First Black Holes

Astronomers have long struggled to explain how supermassive black holes, some weighing billions of times more than the sun, formed so quickly after the Big Bang. The newly identified red dots likely represent a missing stage in that process, when black holes are still embedded in dense gas and growing at their fastest rate.

By catching these objects mid-growth, JWST has revealed a phase that was previously inferred but never directly observed. Rather than rare anomalies, the red dots may mark a common step in the early evolution of galaxies and the black holes at their centers.

If so, the smallest points in JWST’s images are illuminating one of the universe’s biggest mysteries: how its most extreme objects got their start.

Read More: Hubble Discovers Dracula’s Chivito, the Largest-Known Chaotic Planet Nursery

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: