The Great Barrier Reef Experiences Largest Annual Decline in Nearly 40 Years

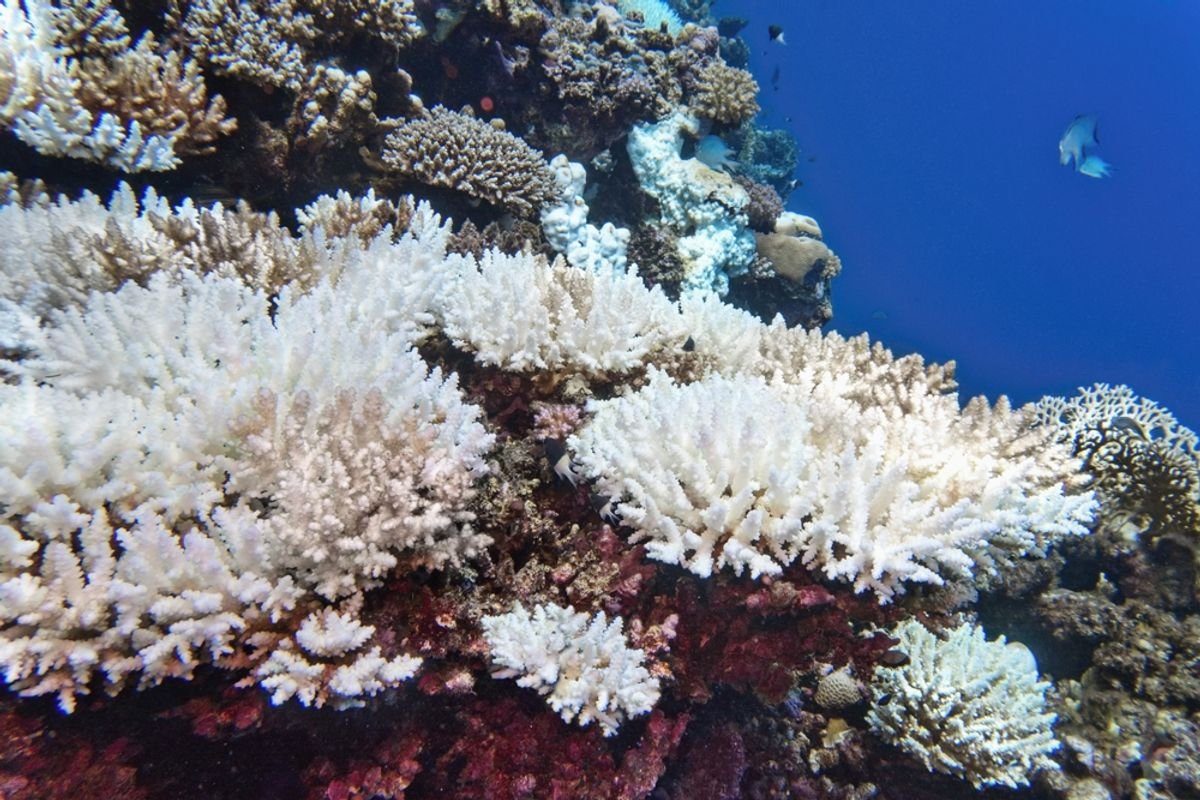

The coral that makes up the Great Barrier Reef has experienced the greatest decline in recorded history. According to yearly surveys that track the state of coral, the reef has declined by up to a third in some parts following a major bleaching event in 2024.

“It’s actually the largest annual decline that we’ve recorded in 39 years in the northern and southern Great Barrier Reef,” says Mike Emslie, a marine biologist at the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS).

Bleaching is a phenomenon that occurs when the coral expels algae that live in a symbiotic relationship with it due to higher-than-normal temperatures. Shallow water is particularly susceptible to bleaching, as hot spells have a large impact on these parts of the sea.

AIMS has been conducting surveys of the Great Barrier Reef since 1986. Bleaching events occurred in 1998, 2002, and then in two consecutive years in 2016 and 2017. A bleaching event also occurred in 2024, leading to the recent losses.

“The interval between these bleaching events is becoming shorter,” Emslie says.

Read More: There is Still Time to Save the Coral Reefs

Surveying the Great Barrier Reef

Emslie has been working on these surveys for more than two decades. They are a huge effort, and surveys still only cover a portion of the overall reef — researchers use a representative sample across the whole of the Great Barrier Reef to estimate status and trends.

The surveys themselves involve manta tow surveys, where researchers are towed behind a boat as they record the state of the reef and fish below. Emslie has done this often, and boats tow him past corals, sharks, and all kinds of other sea life in northeastern Australia.

“I’ve probably been dragged the equivalent distance from here to Hawaii,” he says.

As he goes, he records the state of the reef on underwater paper. They also do fixed site surveys by scuba, including everything from the percentage of bleached coral to the number of crown of thorns sea stars — a species that eats coral and can do a lot of damage.

He’ll also note any cyclone damage and record estimates of reef fishes, including coral trout — an important species for fisheries in the area. In the tow surveys, Emslie and his colleagues also count any sharks, which are mostly reef sharks. In nearly 40 years of surveys, the team has never experienced an attack. He and other researchers record the number of juvenile corals, classified as those less than 5 centimeters long.

“They give us information on the potential for the reef to recover from disturbances,” Emslie says.

The Great Barrier Reef Decline

According to the recent report, which collected data from August 2024 to May 2025, the northern Great Barrier Reef suffered the most loss, with the average hard coral cover decreasing by 39.8 percent. The central Great Barrier Reef experienced a 28.6 percent loss of hard coral cover, while the southern Great Barrier Reef suffered a 26.9 percent loss.

“These are really substantial losses,” Emslie says.

Aerial surveys revealed that 41 percent of the 162 inshore and mid-shelf reefs examined had medium to high bleaching, meaning 10 percent to 60 percent of coral cover was bleached.

These declines in coral cover reveal the extent of cyclones and the large bleaching event that occurred in 2024. The only silver lining of these losses, Emslie says, is that the reefs had been doing well for several years. The last report, in fact, revealed a record high coral cover in some parts of the Great Barrier Reef.

“We’re still above the long-term average in the north and central,” he says.

The trouble is, the reefs won’t have a chance to recover if bleaching events continue to happen more often due to climate change.

“Bleaching and global warming is the greatest threat,” he says. “We’re probably staring down the barrel of annual bleaching events occurring in the near future, and that just doesn’t give the reefs a chance to recover at all.”

Slowing these reef losses down will require a decrease in greenhouse gas emissions, he says. “If we give it a chance, it will recover itself,” Emslie says. “If we don’t do that, the reef as we know it today is unlikely to be around in the next few decades.”

Read More: Reefs Are So Damaged That Fish Have Begun to Use Each Other As Cover

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: