Scientists Are No Closer to Finding a Cure For the Common Cold — Here’s Why

In the mid-1950s, scientist Winston Price identified a virus responsible for the common cold.

Price dubbed his discovery the ‘JH virus’ in honor of his employer (Johns Hopkins University), and set out to find a vaccine that would protect against it.

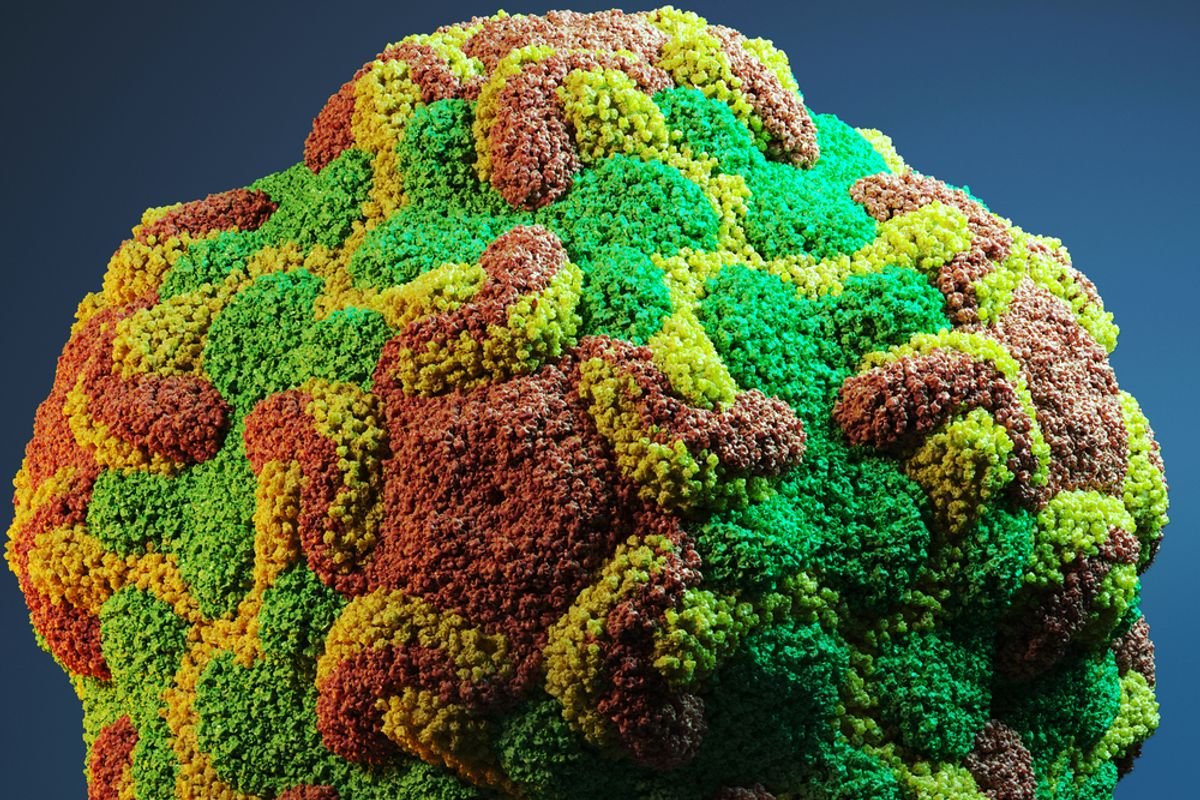

The JH virus is now known as a rhinovirus, and it’s one of hundreds of pathogens responsible for the common cold. Price was unsuccessful in developing a vaccine, and scientists still aren’t any closer to finding a cure for the common cold.

Read More: Mini-Nose Models Sniff Out the Reasons Why RSV Infection Turns Deadly in Infants

Why Isn’t There A Cure For The Common Cold?

When Price identified the JH virus, it was assumed that, because a virus causes colds, a vaccine could be developed to prevent infection. Since then, scientists have learned there are actually hundreds of viruses that cause the common cold.

“There are about 15 respiratory viruses that commonly cause infections in people. Of these 15, several can cause colds. The number one is rhinovirus,” says Ellen F. Foxman, an associate professor of laboratory medicine and immunobiology at Yale School of Medicine. “People talk about rhinoviruses like it’s just one virus, but at least 170 rhinoviruses have been described.”

Rhinoviruses account for approximately half of cold cases. About a quarter of cold infections are caused by coronaviruses, Foxman says.

Although most people associate coronaviruses with COVID-19, they have long been implicated globally in causing the common cold, according to a study published in JAMA.

Beyond rhinoviruses and coronaviruses, enteroviruses and human metapneumovirus also commonly enter the cold-causing chat.

Curing the Common Cold

Scientists working to develop a cure for the common cold face several challenges. It’s not only that hundreds of viruses can cause the common cold, but that rhinoviruses, in particular, can mutate readily.

“It mutates really fast, and it’s always changing,” Foxman says. “Over time, it has evolved. There are a lot of rhinoviruses going around.”

Finding a vaccine that could prevent the common cold would mean creating hundreds of vaccines only to have viruses mutate yet again. These mutating viruses are a challenge for both scientists and our immune systems.

“Within rhinovirus, there are more than 100 different viruses that look different to the human immune system,” Foxman says.

The body’s adaptive immune system does have a memory of sorts. After combating a cold, the immune system develops antibodies that will help fend off future infections. But mutant viruses can be unrecognizable to the immune system. A person will experience cold symptoms while their immune system develops antibodies to target the new pathogen.

How long these new antibodies last can depend both on the virus and the severity of illness the person experienced.

“It’s not like you won’t get infected again, but if you’ve had the virus, it will probably reduce the infectious dose you get. Your body probably won’t be able to kill 100 percent, but it will be able to neutralize it,” Foxman says.

Who Catches a Cold and Who Doesn’t?

During cold and flu season, one member of a household may come down with a virus while the rest nervously await their own fate. In some instances, another family member may catch the cold but have different symptoms. Others may even be spared symptoms.

So why does one person get sick but not another? Especially when they are living in close quarters?

“One reason you may be protected from a virus is if you’ve had exposure or a vaccine,” Foxman says. “But there are also other factors, and that’s what my lab is trying to understand.”

People with certain conditions, like asthma, are more likely to experience symptoms. Similarly, people who smoke cigarettes are more likely to be symptomatic than nonsmokers. Viral load, also called infection dose, can also factor.

“If you get a whole bunch of the virus in your nose, as opposed to just a little bit, that impacts who is going to win the race, your body or the virus,” Foxman says.

People can try to reduce their viral load by washing their hands frequently and wearing a mask. They can also build up their resilience by regularly getting a good night’s sleep. “Maybe you can’t help exposure, but you can with resilience,” Foxman says.

And although a vaccine is not available for the common cold, it is available for other respiratory pathogens like COVID-19, influenza, or RSV, according to the CDC.

This article is not offering medical advice and should be used for informational purposes only.

Read More: Why Do Viruses Like COVID-19 and the Flu Mutate Rapidly and What Does it Mean for Vaccines?

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: