Prehistoric Humans Traded This Rare Green Gem and AI Has Identified Its Surprising Origins

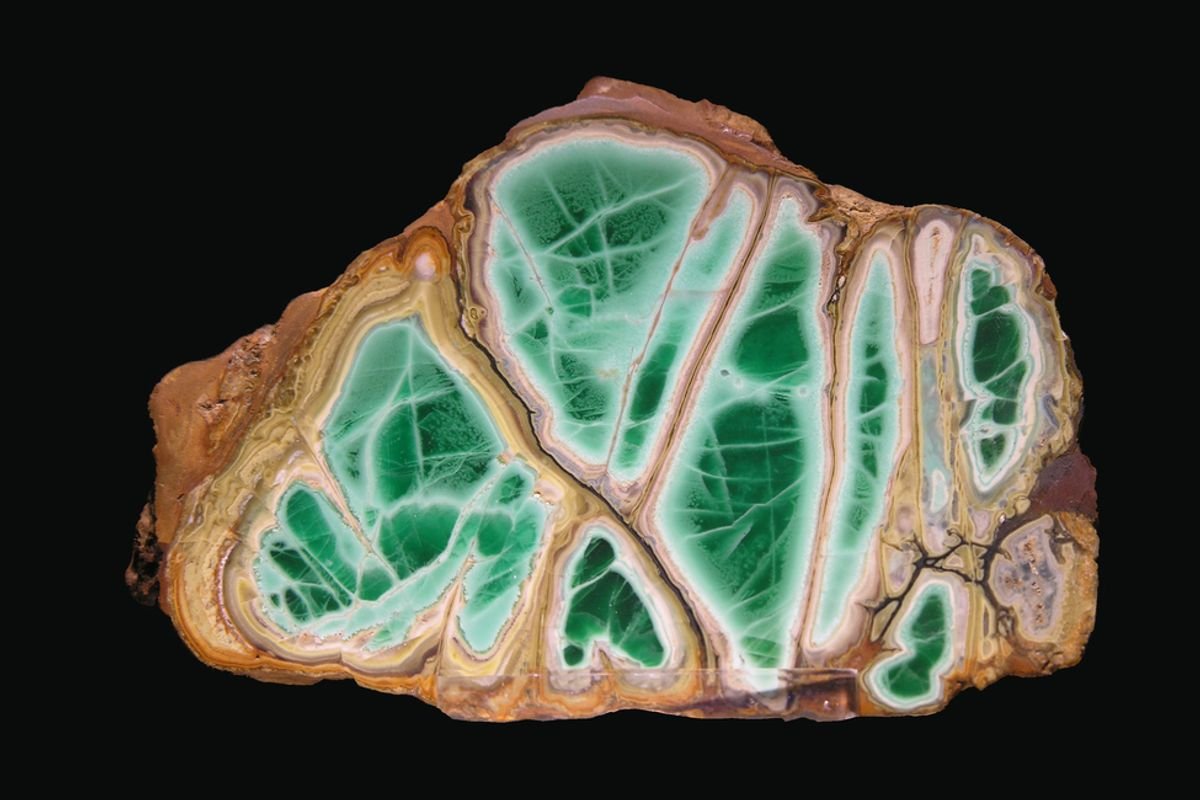

Thousands of years ago, prehistoric human societies traded the rare green mineral variscite. People across Western Europe between the sixth and second millennium B.C. valued the mineral’s distinctive turquoise hue and incorporated it into necklaces, rings, and bracelets. Variscite has been found at various archeological sites across the Iberian Peninsula, but tracing the origins of these finds has proved challenging.

Now, a cross-disciplinary team of AI experts and archeologists from Portugal and Spain has collaborated to build an analysis pipeline that tracks variscite from mine to archeological find, in a recent study published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

“It’s not just about green beads: it’s about using artificial intelligence to tell the human stories of prehistory,” said Daniel Sánchez-Gómez, the study’s lead author and an archeologist at the University of Lisbon, in a press release.

Samples of the Green Gem in Archeological Sites

The researchers had been tracking variscite by comparing geological samples dug from modern mines with ancient variscite samples from archeological sites. In their latest study, the team used portable X-ray fluorescence chemical analysis to determine the elemental composition of 1,778 variscite samples from three ancient mines across modern-day Spain.

They then ran their data through a random forest AI algorithm, which uses a series of decision trees to improve classification accuracy.

“Our model learns to recognize the unique geochemical footprint of each mine,” said Sánchez-Gómez.

After teaching the model to link element signatures to specific mines, the team tested it on 571 variscite beads recovered from archeological sites. The analysis pipeline enabled the team to identify the mine of origin for each bead with 95 percent accuracy.

“It is able to identify where a prehistoric bead comes from, even thousands of years after it was manufactured,” said Sánchez-Gómez.

Read More: The Aztecs Oversaw an Extensive Network of Trade in Precious Obsidian Goods

Surprising Trade Routes

The study’s results showed that archeologists may need to reconsider previously mapped historic trade routes. Previously, a mine near Encinasola in southwestern Spain had been considered the primary site of variscite mining. The new analysis suggests that Encinasola was less important for producing and distributing variscite.

Instead, mines in Gavà and Aliste, in Spain’s Catalonia and Zamora provinces respectively, were likely to be the main sources of the mineral. Variscite found in northern France was geolocated to mines in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, suggesting it was traded along routes crossing the Pyrenees, rather than via shipping passages as previously thought.

Using AI Techniques

Importantly, the team has made their data and the code that powered their analysis available through an open-access repository called Zenodo. This will let other researchers examine the data independently as part of efforts to improve open science.

The team prioritized AI techniques that make their decisions clear to human users, as opposed to those operating in so-called “black boxes.” Carlos Odrizola, the project’s leader and a professor at the University of Seville, said that this approach would increase the utility of their findings to other researchers.

“We have used explainable artificial intelligence techniques, which allow AI models, especially the most complex ones, to explain in a clear and understandable way how they make their decisions. In the case of our research, this means that it not only accurately predicts, but also shows us which chemical elements were decisive in each classification, bringing transparency and rigor to archeological interpretation,” he said in a press release.

The researchers hope their approach could be applied to other materials from archeological sites, such as amber. They also intend to follow variscite’s newly mapped passage across Western Europe to try and determine what made it so highly valued.

Read More: AI Helps Decode Mysterious Prehistoric Cave Markings Known as Finger Flutings

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: