Optical Illusions Can Trick Artificial Intelligence, Just Like They Fool Us

There are lots of visual illusions: an old woman who turns into a young girl, a drawing that’s either a duck or a rabbit depending on how you look at it, and, need I mention the blue and black, or white and gold dress?

Visual illusions are fun, but why do we fall for them? Scientists don’t yet know. But new research on Artificial Intelligence might offer some clues.

Eiji Watanabe, a neurophysiologist at the National Institute for Basic Biology in Okazaki City, Japan, recently discovered that AI can fall for some of the same illusions that trick humans. And that may help scientists understand why we fall for them.

Read More: AI and the Human Brain: How Similar Are They?

Perceiving Visual Illusions

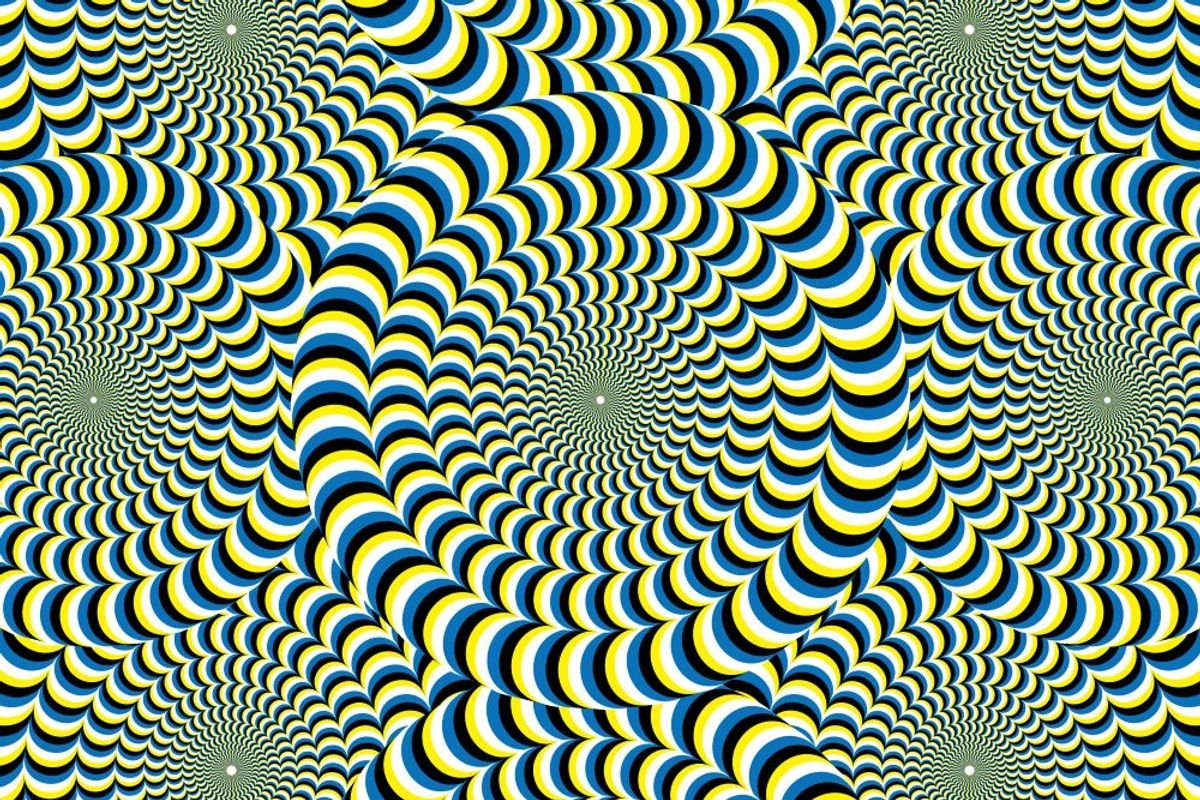

There’s a famous visual illusion called rotating snakes. When you gaze at the image of overlapping concentric circles, the patterns (the snakes) seem to revolve slowly — until, that is, you focus on a single spot (any spot), at which point the snakes freeze, as if they’ve just noticed you’re watching them. The illusion is cool, if a bit headache-inducing.

But what would AI make of that? Watanabe and colleagues wondered, too, so they presented the rotating snakes to PredNet, a deep neural network trained to process visual data, but not trained on illusions. And sure enough, the AI was fooled.

PredNet interpreted the snakes as moving (though it was unable to get them to stop by focusing on one particular spot). When shown a version of the image that doesn’t fool humans, PredNet wasn’t fooled, either.

How Humans Process Illusions

According to Watanabe, these results provide support for the predictive coding (a.k.a. predictive processing) theory of perception. That’s the idea that when we process sensory input — visual input, for example — our brains predict what they expect to see, then adjust for things that don’t match the prediction.

Because the brain doesn’t waste precious resources building an image from scratch, this is a very efficient way to process input. However, it does lead to occasional mistakes, such as getting fooled by very convincing visual illusions.

PredNet is trained to process visual information in a similar fashion. Much like the way Chat GPT calculates what will most likely be the next word in a sentence, PredNet predicts what’s coming in the next frame of a video based on what happened in the previous frame. And that may be why it falls for visual illusions, just like we do. This similarity in processing may be useful not only for understanding visual illusions, but also for better understanding the brain generally.

In their paper published in Frontiers in Psychology, Watanabe and colleagues discussed how using these sensory illusions as an indicator for human perception, deep neural networks could contribute to the development of further brain research.

More Illusions, More Questions

Watanabe’s research raises many interesting questions, Susana Martínez-Conde, a neuroscientist at SUNY Downstate Medical Center who studies perception, told Discover. She and her lab have published research on many visual illusions, including the rotating snakes illusion.

In a 2012 study published in the Journal of Neuroscience, researchers demonstrated that for the rotating snakes illusion to work, you need a triggering event: involuntary eye movements called saccades or microsaccades. “If you don’t move your eyes, the illusion doesn’t work,” she said.

What’s more, not everyone perceives the snakes as moving. Young people are far more likely than older people to see the motion. A 2026 study in Eye and Brain found that when the illusion was shown to two groups of people, one group whose average age was about 23 years and another group whose average age was 74 years, 100 percent of those in the younger group perceived the movement, while only 16 percent of the older group saw movement.

No one knows why the illusion works better for young people, but that does raise some interesting questions about how this illusion works. Martínez-Conde would love to see Watanabe and colleagues use their models to explore these scenarios.

But there’s something even more exciting when it comes to AI and illusions, Martínez-Conde told Discover. AI is being used to create visual illusions. Up until now, most illusions have been created by artists, but a team has now used AI to build a new database of illusions that is much larger than anything that existed before.

“I think [the value of AI] is not just understanding how illusions work, but generating new illusions that we haven’t been able to generate yet,” she concluded to Discover.

Read More: The Brain Sparks Sudden “Aha Moments” As We Try to Decipher Tricky Visual Puzzles

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: