Hidden Heat on Saturn’s Icy Moon Could Help It Sustain Life

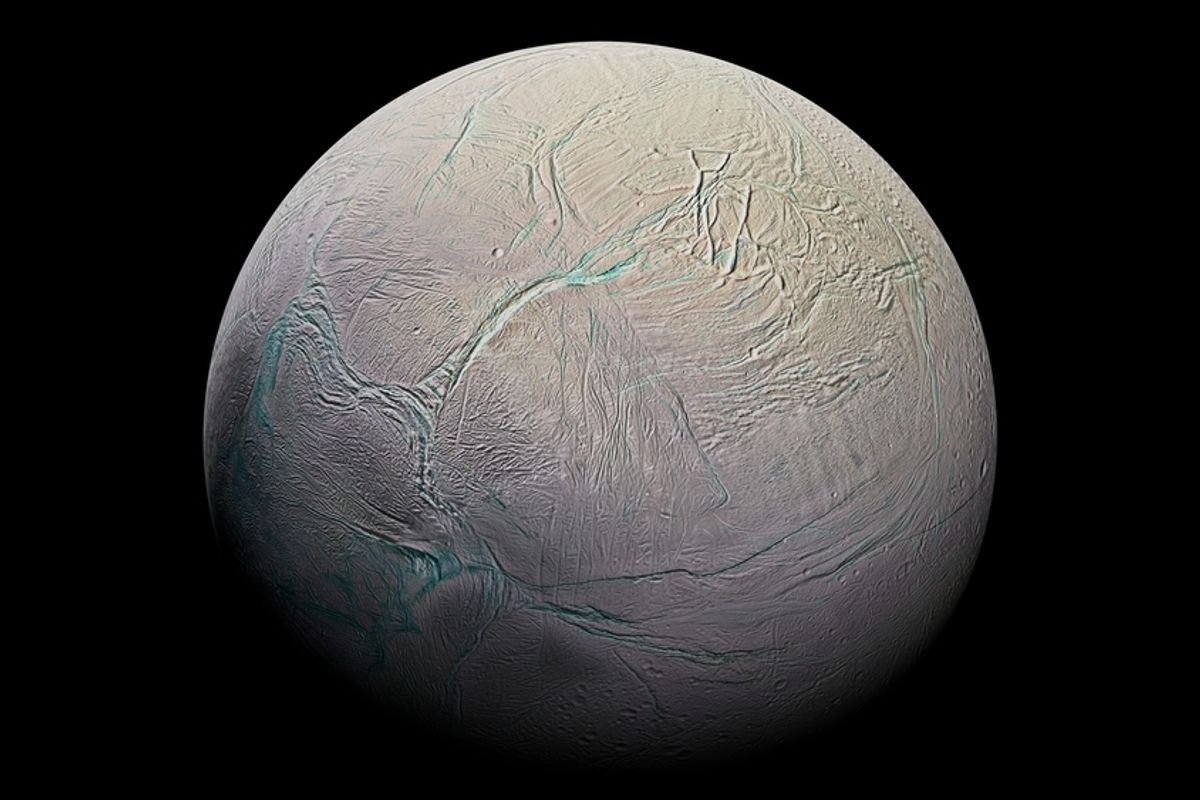

Scientists have long considered Enceladus, one of Saturn’s smaller, icy moons, a strong candidate for life beyond Earth. Now, new research published in Science Advances suggests its hidden ocean may be more stable than previously believed.

Using data from NASA’s Cassini mission, researchers found that Enceladus releases heat from both poles, not just its south. The finding challenges earlier assumptions that the northern hemisphere was geologically quiet, showing instead that the moon is warmer and more active than expected.

“Enceladus is a key target in the search for life outside the Earth, and understanding the long-term availability of its energy is key to determining whether it can support life,” said Georgina Miles, lead author of the paper, in a press release.

Read More: European Spacecraft JUICE Travels to Jupiter’s Icy Moons

Tidal Forces Power a Global Ocean

Enceladus ranks among the most active worlds in the solar system. Beneath its ice crust lies a global ocean of salty water, which helps drive the moon’s internal heat and surface activity. The mix of liquid water, warmth, and chemicals such as phosphorus and complex hydrocarbons makes it a leading candidate for life beyond Earth.

That ocean can only persist if its energy stays in balance. As Saturn’s gravity pulls on Enceladus, the moon flexes slightly, producing heat through tidal friction. Too little, and the ocean could freeze; too much, and the system could become unstable. Until now, measurements of heat loss came only from the south pole, where plumes of vapor and ice rise from long surface fractures. The north was thought to be inactive.

Infrared Data Exposes Northern Warmth

Cassini’s infrared data showed otherwise. Comparing images of Enceladus’ north pole from the dark winter of 2005 and the bright summer of 2015, researchers found the surface was about 7 Kelvin (roughly 7 °C, or 12 °F) warmer than models predicted — a small but consistent difference that points to heat leaking from the ocean below.

That flux amounts to about 46 milliwatts per square meter, about two-thirds the heat flow through Earth’s crust. Scaled across the moon, it equals about 35 gigawatts of energy loss, roughly the power output of 10,500 wind turbines or 66 million solar panels.

The balance between energy gained and lost suggests that Enceladus’ ocean remains stable over geological timescales, able to stay liquid and dynamic beneath its frozen crust.

“Eking out the subtle surface temperature variations caused by Enceladus’ conductive heat flow from its daily and seasonal temperature changes was a challenge, and was only made possible by Cassini’s extended missions,” said Miles, in the press release. “Our study highlights the need for long-term missions to ocean worlds that may harbour life, and the fact the data might not reveal all its secrets until decades after it has been obtained.”

A Stable Ocean Fit for Life

“Understanding how much heat Enceladus is losing on a global level is crucial to knowing whether it can support life,” added Carly Howett, corresponding author of the paper. “It is really exciting that this new result supports Enceladus’ long-term sustainability, a crucial component for life to develop.”

The next step is to determine how long the ocean has existed — whether it’s an ancient sea that’s endured for billions of years or a more recent phenomenon. The study also used Cassini’s thermal data to estimate the moon’s ice thickness, which ranges from 20 to 23 kilometers (13 to 14 miles) at the north pole and 25 to 28 kilometers (15 to 17 miles) globally, slightly thicker than earlier estimates.

Read More: ‘Tiger Stripes’ on a Saturn Moon Could Be Even More Unique Than Previously Thought

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: