Bacteria-Killing Viruses Turn into Better Antibiotic Fighters in Space

Microorganisms have evolved together for millennia under Earth’s gravitational conditions, fundamentally shaping their physiology. But what would happen to their dynamics if they lived under space conditions, without gravity laying the foundation for their biological processes?

Researchers from the University of Wisconsin–Madison set out to explore exactly that. In a study published in PLOS Biology, they found that under near-weightless conditions, virus–bacteria interactions played out differently than they do on Earth. These changes could be traced through unique genetic mutations never before observed under normal gravity. Surprisingly, the findings may help us develop new ways to fight antibiotic-resistant bacteria on Earth.

“Space fundamentally changes how phages and bacteria interact: infection is slowed, and both organisms evolve along a different trajectory than they do on Earth,” added the study authors in a news release.

Viruses That Kill Bacteria

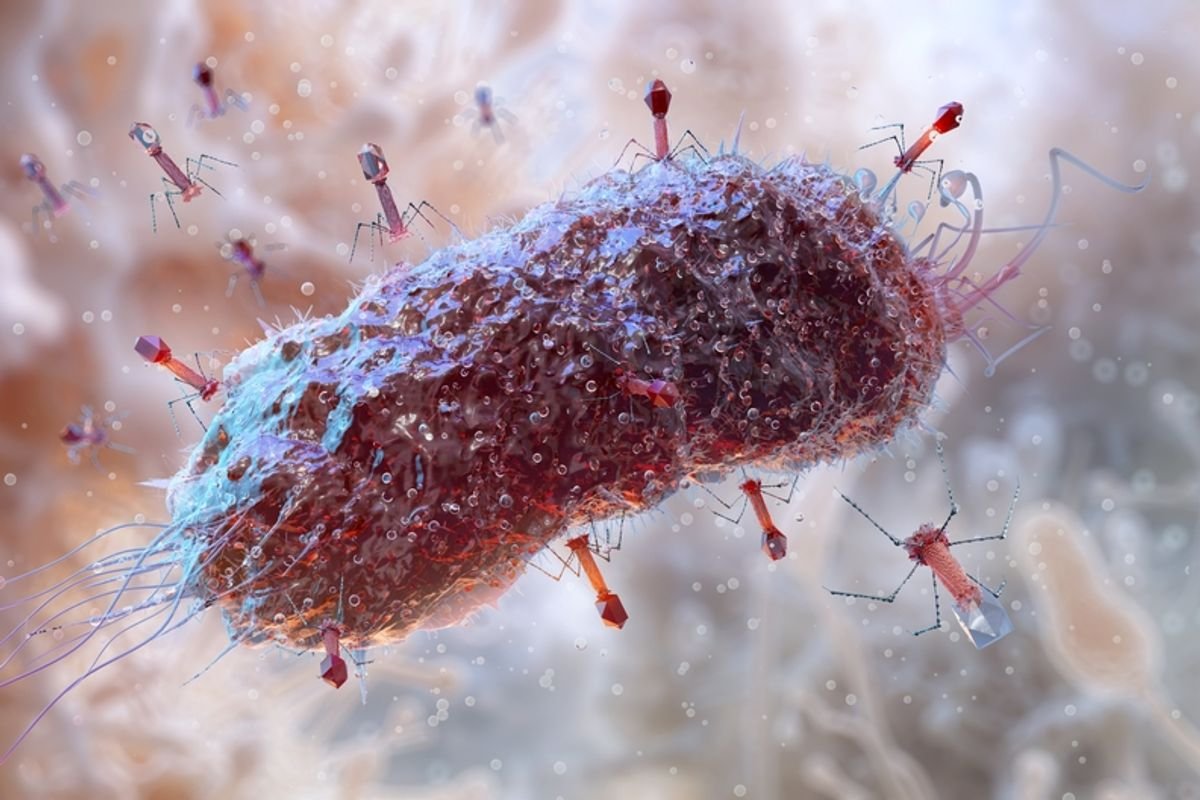

Relationships between microorganisms are just as complex as those among plants or animals. Some viruses, called bacteriophages (or simply phages), are specialized to infect bacteria. They’ve co-evolved with their bacterial hosts for billions of years and play a crucial role in keeping bacterial populations in check across ecosystems.

Because phages can kill bacteria without harming human cells, scientists have long been interested in their medical potential, especially as antibiotic resistance becomes a growing global threat. The World Health Organization recognizes phages as a promising tool against antimicrobial resistance, though they’re still mostly used as a last-resort treatment. Before phage therapy can become mainstream, researchers need a better understanding of how phages evolve and interact with bacteria.

Most of that research happens under “normal” Earth conditions. But the Wisconsin–Madison team wondered what might happen if one of the most constant forces shaping life — gravity — was removed from the equation.

Read More: A Medical Emergency 250 Miles Above Earth Forces NASA to Make a Rare Decision

Space-Associated Mutations Can Fight Stubborn E. Coli Strains

To test this, the researchers compared two identical experiments. In both, E. coli bacteria were infected with a well-studied phage called T7. One set of samples stayed on Earth, while the other was sent to the International Space Station (ISS).

At first, the space-based experiment behaved differently. Infection by the T7 phage was delayed in microgravity, suggesting that weightlessness slows down the usual virus-bacteria interaction. But after that initial lag, the phage successfully infected the bacteria.

The real surprise came when the researchers sequenced the genomes of both the bacteria and the viruses. The samples grown aboard the space station accumulated genetic mutations that were distinct from the Earth-based controls. In space, the phages gradually picked up mutations that appeared to improve their ability to infect bacteria.

At the same time, the E. coli bacteria also adapted. They developed mutations that seemed to help them survive both phage attacks and the unusual stresses of a near-weightless environment.

To dig deeper, the team used a technique called deep mutational scanning to examine changes in one key phage protein responsible for binding to bacteria. This revealed even more dramatic differences between space-grown and Earth-grown phages. Follow-up experiments showed something remarkable: Some of the space-associated mutations made the phages more effective against E. coli strains that cause urinary tract infections in humans, strains that are normally resistant to T7.

Space Research Valuable to Understand Life On Earth

The study highlights how space research can lead to unexpected breakthroughs closer to home by removing physical factors often overseen in biochemical research.

“By studying those space-driven adaptations, we identified new biological insights that allowed us to engineer phages with far superior activity against drug-resistant pathogens back on Earth,” said the study authors.

The team expressed optimism about continuing phage research aboard the ISS, leaving us eager for the next unexpected insights into how microbial life evolves beyond the physical boundaries of Earth.

Read More: Viruses on Plastic Pollution May Be Fueling Antibiotic Resistance

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: