ADHD Drugs May Target Reward Centers, Not Attention Networks

According to the CDC, around one in ten (11.4 percent) children have been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), millions of whom take prescription medication, like Ritalin and Adderall, to manage symptoms such as inattentiveness and impulsivity.

It is thought that these stimulants target attention networks, but new research suggests that may not actually be the case. According to researchers writing in Cell, medications instead target the brain’s reward and wakefulness centers, relieving symptoms of ADHD by upping arousal levels, increasing motivation, and, in some cases, mimicking the power of a good night’s sleep.

“Essentially, we found that stimulants pre-reward our brains and allow us to keep working at things that wouldn’t normally hold our interest — like our least favorite class in school, for example,” Nico U. Dosenbach, the David M. & Tracy S. Holtzman Professor of Neurology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, said in a statement.

Read More: How People With ADHD Can Harness Mind Wandering and Enhance Creativity

Lighting Up The Brain’s Reward And Arousal Centres

To determine how the brain responds to stimulants, researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis compared MRI results from 5,795 children aged 8 to 11, collected as part of the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) Study. This included 337 children who had taken stimulants on the morning of the scan and a further 76 who had a prescription but had not taken medication that day. The remainder had neither been prescribed stimulants nor taken stimulants before the scan.

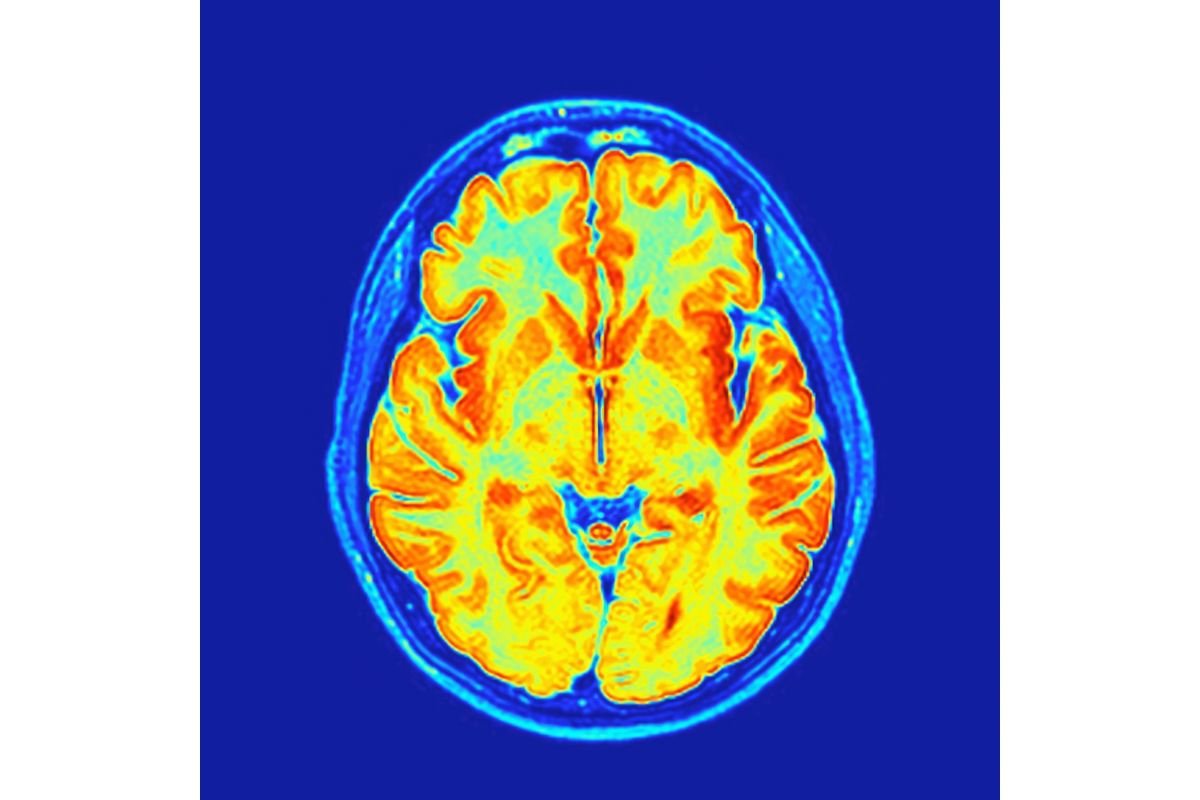

While the study’s authors noticed few differences between those who had taken stimulants and those who had not when it came to regions involved with attention (such as the dorsal attention network and prefrontal cortex), there were notable divergences in areas of the brain associated with reward and wakefulness. Rather than enhancing the brain’s ability to focus, the medication may work by increasing drive and boosting motivation, say researchers.

“I prescribe a lot of stimulants as a child neurologist, and I’ve always been taught that they facilitate attention systems to give people more voluntary control over what they pay attention to,” Benjamin Kay, an assistant professor of neurology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, said in a statement.

“But we’ve shown that’s not the case. Rather, the improvement we observe in attention is a secondary effect of a child being more alert and finding a task more rewarding, which naturally helps them pay more attention to it,” Kay added.

A follow-up study involving five adults without ADHD and without a history of taking prescriptive stimulants seemed to confirm these results. It was areas of the brain linked to reward and wakefulness that appeared to “light up” in response to the medication.

Mimicking The Effects Of Sleep

Helpfully, the ABCD Study also provides data on grades, sleep patterns, and cognitive test results. These revealed interesting parallels between ADHD medication and sleep.

There were two groups who appeared to benefit from stimulants: those with ADHD and those who received less than the recommended 9 hours of sleep a night. Sleep-deprived children who took medication performed better at school than sleep-deprived children who didn’t, whether or not they had an ADHD diagnosis. In contrast, stimulants had no notable effect on neurotypical children who received the appropriate amount of shuteye.

The researchers point out that medication is not a suitable alternative for sleep and may simply disguise certain symptoms (such as inattentiveness) without addressing the long-term costs associated with sleep deprivation.

“Not getting enough sleep is always bad for you, and it’s especially bad for kids,” said Kay.

At the same time, he encourages clinicians to consider the amount of sleep a child is getting when diagnosing ADHD.

This article is not offering medical advice and should be used for informational purposes only.

Read More: ADHD Diagnoses Seem to Have Increased on the Internet – Is It Really That Common?

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: