A Marine Predator the Size of a Bus Patrolled Ancient Rivers 66 Million Years Ago

For decades, mosasaurs have been understood as among the dominant predators of the Cretaceous seas — marine reptiles that could reach 11 meters in length and patrol the waters of the Western Interior Seaway. But a new analysis of a tooth from North Dakota suggests that at least one lineage didn’t remain confined to the sea.

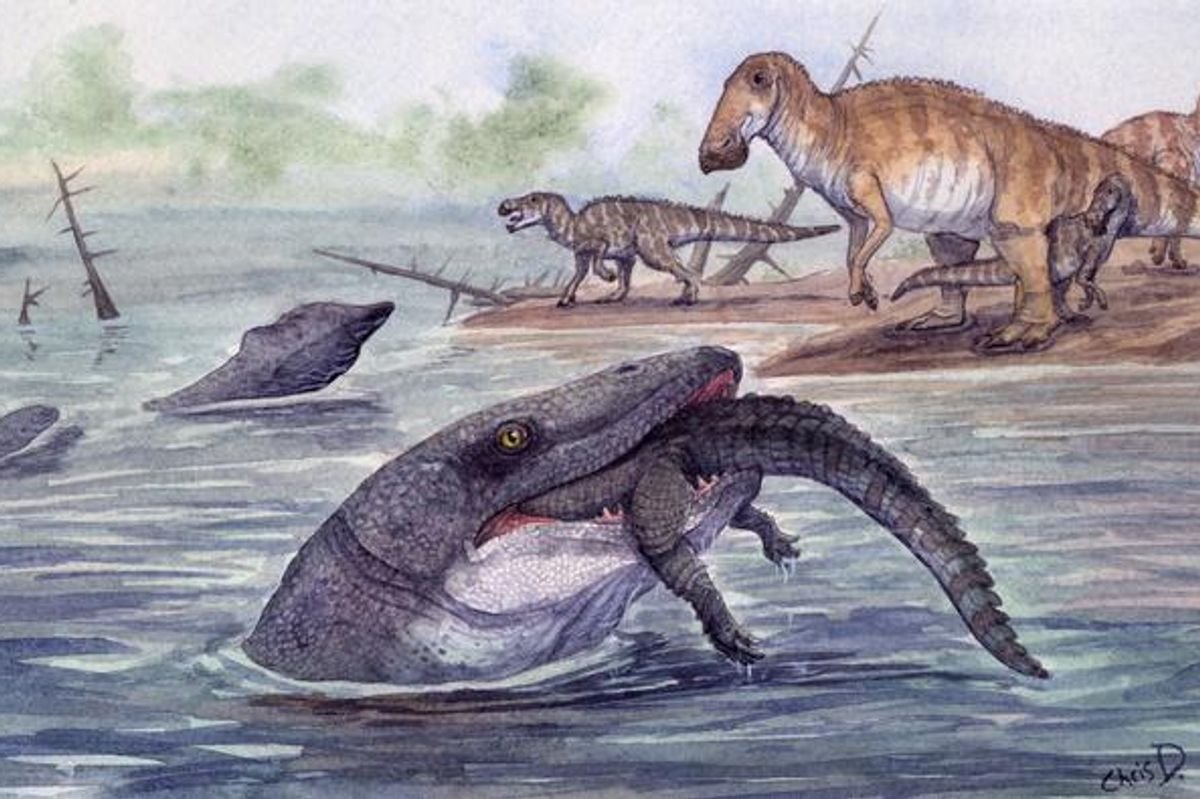

Reported in BMC Zoology, the findings indicate that this predator ventured upstream, navigating river channels that flowed through the Hell Creek region more than 66 million years ago. The tooth, uncovered in 2022 from an ancient river deposit, was found with a T. rex tooth and part of a crocodilian jaw in a region where Edmontosaurus bones were also common — an unlikely combination that hinted at a much more complex ecosystem than scientists expected.

“The isotope signatures indicated that this mosasaur had inhabited this freshwater riverine environment. When we looked at two additional mosasaur teeth found at nearby, slightly older, sites in North Dakota, we saw similar freshwater signatures. These analyses shows that mosasaurs lived in riverine environments in the final million years before going extinct,” said Melanie During, a coauthor of the study, in a press release.

Freshwater Signatures Rewrite Mosasaur Habitats

To understand how a marine reptile ended up in a river deposit, the team compared the mosasaur tooth with nearby fossils of similar age. At Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, they analyzed oxygen, strontium, and carbon isotopes preserved in the enamel, a method that can reveal both habitat and feeding behavior.

Mosasaur tooth found in Hell Creek

(Image Credit: Trissa Shaw/CC BY)

The results pointed clearly away from the open sea. The tooth carried elevated levels of the lighter oxygen isotope ¹⁶O, and its strontium ratios matched freshwater conditions rather than marine ones. Together, they suggested an animal living primarily in rivers.

“Carbon isotopes in teeth generally reflect what the animal ate. Many mosasaurs have low ¹³C values because they dive deep. The mosasaur tooth found with the T. rex tooth, on the other hand, has a higher ¹³C value than all known mosasaurs, dinosaurs and crocodiles, suggesting that it did not dive deep and may sometimes have fed on drowned dinosaurs,” said During.

There was no evidence the tooth had been swept in from distant marine sediments, implying the animal’s life — and death — played out in the river itself. Similar freshwater signatures in two slightly older teeth from the area point to a recurring presence rather than a lone stray, suggesting that some mosasaurs were using these rivers in the final stretch of the Cretaceous.

Read More: The End of the Dinosaurs: What Was the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction?

Why Changing Waters Opened New Habitats for Giant Mosasaurs

The freshwater signal in the tooth aligns with larger environmental changes reshaping North America at the end of the Cretaceous. As the Western Interior Seaway retreated, rivers poured increasing amounts of freshwater into its basin, creating a surface layer that steadily lost salinity. Comparisons with nearby fossils show gill-breathers tied to brackish water, while lung-breathers — including mosasaurs — lack those signatures, pointing to a reliance on the surface freshwater layer.

In that changing environment, a predator the size of the Hell Creek mosasaur would have been hard to overlook. The tooth points to an animal approaching 11 meters long — about the size of a city bus — and likely part of the Prognathodontini, a group with bulky heads, sturdy jaws, and a reputation for opportunistic hunting.

“The size means that the animal would rival the largest killer whales, making it an extraordinary predator to encounter in riverine environments not previously associated with such giant marine reptiles,” said Per Ahlberg, a coauthor of the study.

Together, the chemical evidence and environmental context suggest that as the seaway receded, some mosasaurs adapted with it — following newly formed rivers and exploiting habitats long assumed to lie beyond their reach.

Read More: A Real-Life Dragon: How A Newly Classified Mosasaur Got Its Legendary Name

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: