A 233-Million-Year-Old Fossil Reveals How Pterosaurs Learned to Fly

Pterosaurs entered the air deep in the Triassic, more than 220 million years ago. Birds followed much later, with early forms such as Archaeopteryx appearing roughly 150 million years ago. Although both groups mastered flight, how their brains evolved to support it followed very different paths.

That contrast is now coming into sharper focus with new research published in Current Biology. By tracing the pterosaur brain back more than 230 million years, the study shows that their earliest relatives already showed signs of enhanced visual processing — even before the full suite of brain structures needed for flight had fully formed.

“The breakthrough was the discovery of an ancient pterosaur relative, a small lagerpetid archosaur named Ixalerpeton from 233-million-year-old Triassic rocks in Brazil,” said Mario Bronzati, lead author of the study, in a press release.

“Now, with our first glimpse of an early pterosaur relative, we see that pterosaurs essentially built their own ‘flight computers’ from scratch,” added co-author Lawrence Witmer.

Reconstructing Pterosaur Brains from Fossils

To follow how the pterosaur brain took shape, the team digitally reconstructed the brain cavities of more than three dozen animals. Their sample included pterosaurs, their closest non-flying relatives, early dinosaurs, and living birds and crocodilians.

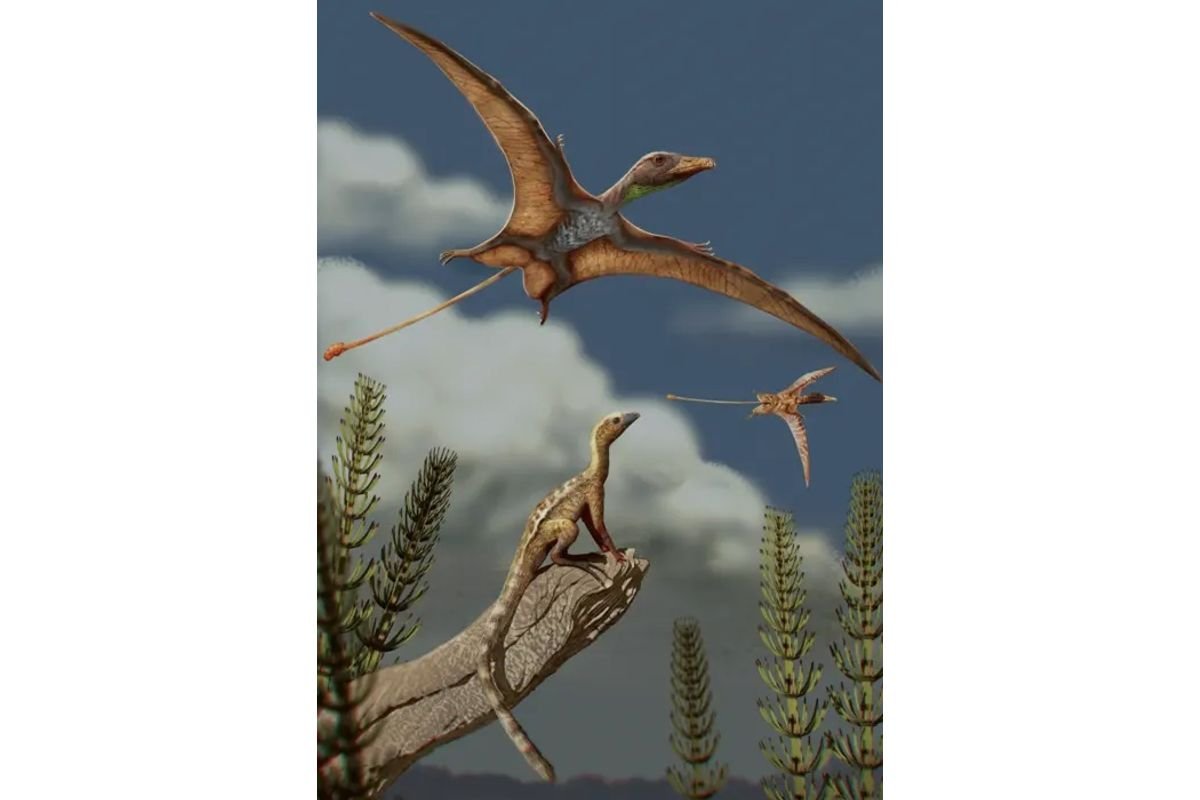

3D reconstructions of the brains of pterosaur (top) and a lagerpetid (bottom) from the Late Triassic period (around 215 million years ago).

(Image Credit: Rodrigo Müller, Mario Bronzati, Matheus Fernandes)

Using high-resolution microCT scans, the researchers created detailed 3D models of these brain spaces, known as endocasts. By comparing their size and shape across species, the team could track how different brain regions changed through deep time.

“Then, using statistical analysis of the size and 3D shape of their cranial endocasts, we were able to map the stepwise changes in brain anatomy that accompanied the evolution of flight,” said co-author, Akinobu Watanabe, in the press release.

The First Steps Toward Flight

Fossils of Ixalerpeton offered the clearest window yet into the earliest stages of pterosaur brain evolution. Although this small reptile never flew, its brain shows that some of the sensory groundwork for flight was already forming before wings ever appeared.

The fossil reveals an expanded optic region of the brain, pointing to improving visual processing early on. But it lacked the enlarged flocculus — the structure that helps stabilize vision and coordinate movement during flight — a feature that only appears later in true pterosaurs.

Together, these differences show that the brain upgrades linked to flight didn’t arrive all at once. Vision sharpened first, while the full neurological control system followed later, after wings were already in place.

“While there are some similarities between pterosaurs and birds, their brains were actually quite different, especially in size,” said co-author Matteo Fabbri. “Pterosaurs had much smaller brains than birds, which shows that you may not need a big brain to fly.”

Rather than scaling up overall, the pterosaur brain became increasingly specialized. The architecture of specific regions mattered more than volume.

“It apparently doesn’t take a large brain to get into the air, and the later brain expansion in both birds and pterosaurs was likely more about enhancing cognition than about flying itself,” said Witmer.

Read More: 150-Million-Year-Old Baby Pterosaurs With Broken Wings Help Solve a Centuries-Old Dinosaur Mystery

Rewriting Early Flight Evolution

Finds like this are narrowing one of paleontology’s long-standing blind spots: how the earliest relatives of pterosaurs and dinosaurs actually lived and functioned.

“Discoveries from southern Brazil have given us remarkable new insights into the origins of major animal groups like dinosaurs and pterosaurs,” said co-author Rodrigo Temp Müller. “With every new fossil and study, we’re getting a clearer picture of what the early relatives of these groups were like, something that would have been almost unimaginable just a few years ago.”

Read More: A Crocodilian Took a Bite Out of a Pterosaur 76 Million Years Ago

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: