2,700-Year-Old Total Solar Eclipse Observations Give Insight to Our Ancient Solar System

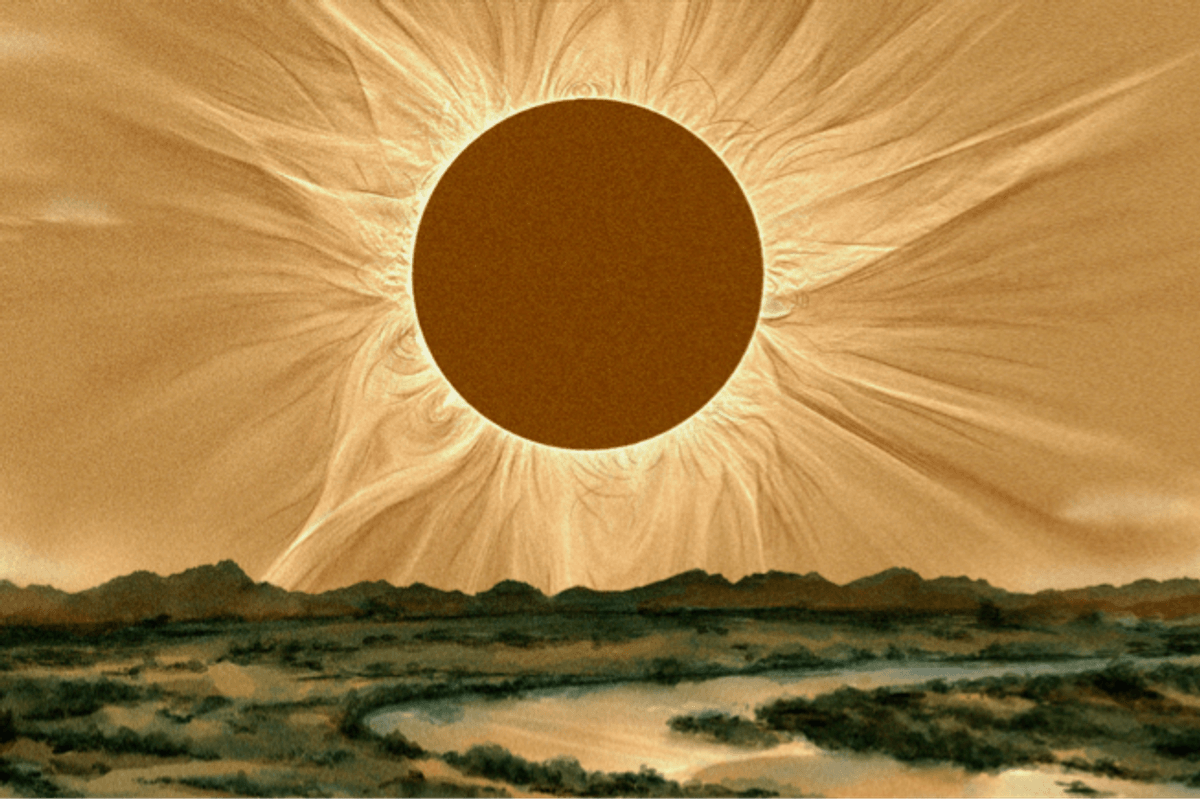

Researchers have returned to the records of a rare sky phenomenon seen in China around 2,700 years ago. Applying modern astronomy methods and measurements to recreate the appearance of the sun in Qufu, the capital city of the ancient state of Lu, on July 17, 709 B.C.E., the team has confirmed ancient records of a total solar eclipse and corona.

Reported in Astrophysical Journal Letters, the results refine and support recent reconstructions of Earth’s rotation and the sun’s activity in the 8th century B.C.E., hinting that one was faster while the other was weaker than they are today in the lead-up to the eclipse.

“Some of our ancestors were very skilled observers,” said Meng Jin, a study author from the Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Laboratory, according to a press release. “When we combine their careful records with modern computational methods and historical evidence, we can potentially find new information about our planet and our star from thousands of years ago.”

Read More: These 5 Ancient Cultures Thought Solar Eclipses Were Omens and Prophecies

Extensive Eclipse Archives

This Ancient Chinese text, dating back to 709 B.C.E., is from the Spring and Autumn Annals and has some of the oldest written records of a total solar eclipse.

(Image Credit: National Archives of Japan, CC BY)

In ancient China, it was commonly thought that strange sky occurrences, such as eclipses, auroras, and other oddities, served as omens for the state. This caused emperors, their courts, and courtiers to create comprehensive records of the skies and to maintain them over time, leaving China with one of the most extensive eclipse archives from antiquity.

According to these accounts, something strange was spotted in the sky in Qufu in 709 B.C.E. Reported in two separate registers — a chronicle titled the “Spring and Autumn Annals,” which was compiled around two to three centuries after the event, and another chronicle titled the “Hanshu,” which was compiled a couple of centuries after that — the event represents one of the earliest total solar eclipses, and one of the earliest coronas, on record that’s attributable to an actual date.

“What makes this record special isn’t just its age, but also a later addendum in the ‘Hanshu’ (‘Book of Han’) based on a quote written seven centuries after the eclipse. It describes the eclipsed sun as ‘completely yellow above and below,’” said Hisashi Hayakawa, another study author from Nagoya University, according to the release. “This addendum has been traditionally associated with a record of a solar corona. If this is truly the case, it represents one of the earliest surviving written descriptions of [a] solar corona.”

Read More: An Omen of Doom and Other Myths Surrounding Solar Eclipses

Eclipse Coordinate Correction

Turning to the coordinates of Qufu and the methods of modern astronomy to corroborate the record, the researchers failed to find any evidence of a total solar eclipse at first. However, after consulting archaeological records and reports, they recognized that their coordinates for Qufu were wrong, pointing to a location around five miles away from the ancient city.

Adjusting the coordinates and re-running the calculations, the team eventually concluded that a total eclipse was seen in Qufu in 709 B.C.E.

“This correction allowed us to accurately measure the Earth’s rotation during the total eclipse, calculate the orientation of the sun’s rotation axis, and simulate the corona’s appearance,” Hayakawa added in the release.

Read More: Why Astronomy is Considered the Oldest Science

Ancient Insights into the Solar System

Taken together, the results not only clarify the occurrence and the timing of the total solar eclipse; they also revise the estimations of the Earth’s rotation speed, which was much faster in antiquity, and substantiate the estimations of the sun’s activity, which was much weaker in antiquity, too.

In fact, while the researchers caution that the later record of the corona is a little less certain, thanks to its relative age and its lack of certification in similar sources, the shape and structure of the corona — if it actually appeared — suggest that the eclipse occurred after the sun recovered from a period of reduced activity from around 808 B.C.E. to around 717 B.C.E. When the eclipse appeared, the sun had returned its regular solar cycle, and thus its regular activity, the team says, with its magnetism ramping up in 709 B.C.E.

According to the researchers, the results solve several important mysteries about our Solar System, and about the movement and activity of the planets and stars within it. They also stress that ancient records are imperative reservoirs of astronomical information, offering insights into our world today and thousands of years ago.

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: